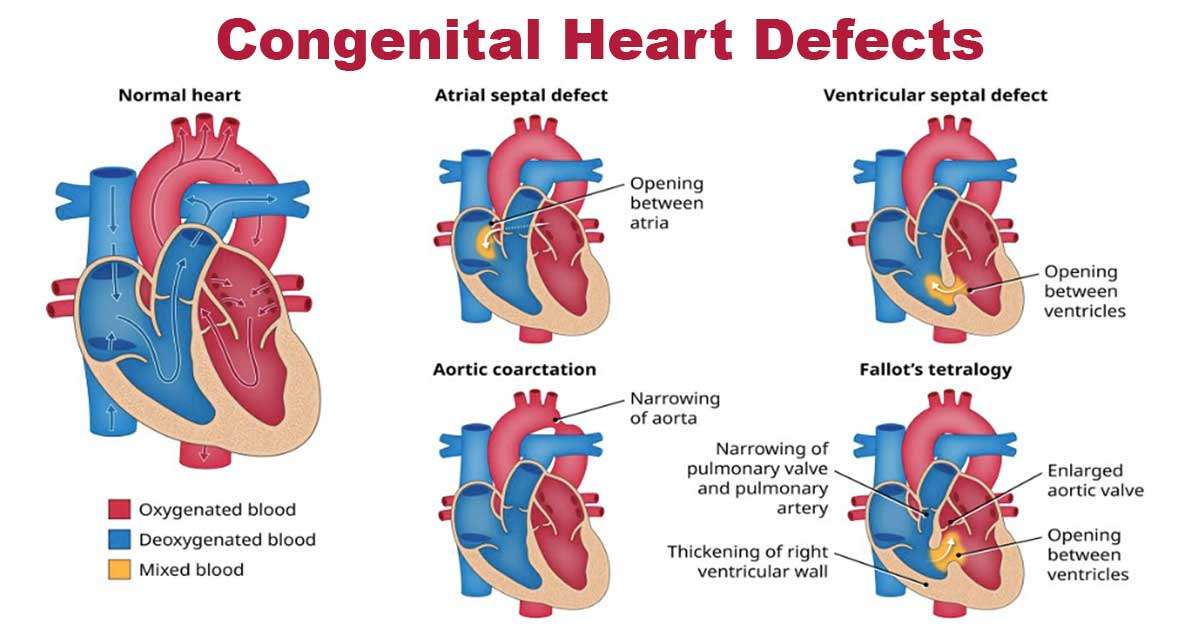

Congenital heart defects are structural abnormalities in the heart that occur at birth (CHDs). Congenital conditions are present at birth. Many complications arise when a baby’s heart does not develop normally during pregnancy. Heart abnormalities are the most common type of congenital malformation. Congenital cardiac defects can have an impact on how the heart pumps blood. They can cause blood flow to slow, change direction, or even stop.

In the United States, congenital heart disease (CHD) affects 0.8% of live births and is the leading cause of birth abnormalities. However, approximately 13 newborns are diagnosed with congenital heart disease in the United Kingdom daily. This indicates a problem with the development of the heart or the great arteries while the baby is still in the womb.

Congenital heart disease is a congenital disability involving the heart or major arteries (CHD). The most common cause of congenital heart disease is a defect in embryogenesis between weeks three and eight of pregnancy, when the major circulatory systems mature and begin to function. Premature babies and stillbirths frequently have significant cardiac abnormalities, with the most severe anomalies making intrauterine survival impossible.

Adults are more likely than children to be diagnosed with congenital heart disease, and the prevalence of complex CHD is rising as people of all ages live longer. Because of advances in therapy and intervention, 85-90% of these children can expect to live to adulthood. While much effort has been put into characterizing and improving newborn and pediatric survival, little is known about the demographics, long-term outcomes, and comorbidities of the adult CHD (ACHD) population in the United States.

However, defects that affect only a small portion of the heart or a specific region are frequently tolerated during embryonic development and can even result in a live birth. This category includes uterine atony, septal abnormalities, and unilateral obstructions.

There are issues with the outflow system. ASDs and VSDs are examples of septal defects, or “holes in the heart” (VSDs). Stenosing lesions, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome, can affect the entire heart chamber and the valve. When the major vessels exit the ventricle in the wrong direction, this is an example of an abnormality in the outflow tract. These congenital heart defects usually manifest clinically after birth, when the circulation shifts from fetal to perinatal.

Congenital heart disease diagnosis

Congenital heart disease includes many foetal development-related cardiac abnormalities. The defect’s physiologic importance determines the onset age. After birth, hypoxemia or hemodynamic collapse can occur. Some develop a new murmur or congestive heart failure months later. Schoolchildren may miss asymptomatic lesions. Prenatal ultrasounds can reveal cardiac defects.

Congenital cardiac disease must be diagnosed early. A focused history and physical examination start the workup. Classifying heart murmurs aids in cardiac diagnosis. Cyanosis, tachypnea, irregular pulses, and failure to thrive suggest cardiovascular disease. Congenital heart disease causes eating issues, irritability, and respiratory infections.

Electrocardiograms and CXRs are common tests (EKG). CXR can detect heart issues. Heart size, pulmonary markings, aortic arch-sidedness, and situs anomalies may signal other problems (the heart located in the mid- or right chest rather than the specific location in the left chest). EKGs detect abnormal heartbeats, axis deviation, atrial enlargement, and ventricular hypertrophy. Transthoracic echocardiography provides surgical planning anatomical detail. Cardiac catheterization, cMRI, and CTA are additional diagnostic tests for flow, pressure, resistance, and anatomic detail.

What causes congenital heart disease?

According to researchers, many causes of congenital heart defects remain unknown. They know that changes in a baby’s genes can cause cardiac problems in rare cases. The messed-up genes may be passed down from parents or evolve in utero. If any of the following apply to the child, he or she may be born with a congenital heart defect:

- Your overall health, particularly in the run-up to and during pregnancy.

- Having diabetes prior to pregnancy or during the first three months of pregnancy (late-onset diabetes does not offer a major risk for heart defects). Your baby is less likely to have a heart defect if you maintain blood sugar levels before and during pregnancy.

- Have phenylketonuria (PKU), a rare hereditary disorder affecting protein metabolism. If you have PKU and are trying to conceive, a low-protein diet before conception can help reduce your child’s risk of being born with a heart defect.

- Getting pregnant and contracting rubella (German measles).

- If you smoked during your pregnancy or were exposed to secondhand smoke (breathing smoke from another smoker).

- A few medications include retinoic acid for acne and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for hypertension. If you are conceiving or trying to conceive, inform your doctor about all your medications.

- Your genetic code and the family tree must be considered. The majority of congenital heart disease cases are sporadic and not inherited. However, if you or the other parent has a congenital heart defect or already have a child with a congenital heart defect, the chances of having a baby boy or girl with a congenital heart defect increase.

Congenital heart disease symptoms

Congenital heart defects do not cause pain. It is critical to remember that symptoms can vary greatly depending on the defects’ nature, extent, and severity. Cyanosis is a common symptom of congenital heart disease, characterized by a bluish hue to the skin, lips, and fingernails. A lack of oxygen in the blood causes this condition. Infants may exhibit the following symptoms:

- Cyanosis

- Weakness

- Unusual drowsiness

- Rapid or difficult breathing

- Low blood pressure

Types of congenital heart defects

There are various types of congenital heart defects. They can occur in a single location on the heart or spread to other areas. Heart defects are relatively common, with major artery defects being the most common cause. Birth heart abnormalities can range from completely harmless and never requiring treatment to being fatal.

- Septal defects are holes in the heart’s wall that separate the left and right sides.

- Heart valve defectsare diseases that affect the heart’s valves, which regulate blood flow.

Congenital heart defects refer to the most severe types of congenital heart defects. Most newborns with these defects will require surgery within their first year. On the other hand, milder forms of heart abnormality may not manifest themselves until puberty or later in life.

Acyanotic or less severe congenital heart defects are classified as cyanotic congenital heart disease, ductal-dependent congenital heart disease, critical congenital heart disease, and other congenital heart problems. Cardiomyopathy cyanotic congenital: A newborn with certain congenital cardiac abnormalities will be blue at birth (called cyanosis). Deoxygenated blood leaks into the body, causing the blue tint. Cyanotic heart defects include:

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Transposition of great arteries

- Tricuspid atresia

- Total anomalous pulmonary venous return

- Truncus arteriosus

- Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

All of these diseases require surgery by the first year of life. They may even require several operations to enable proper heart function.

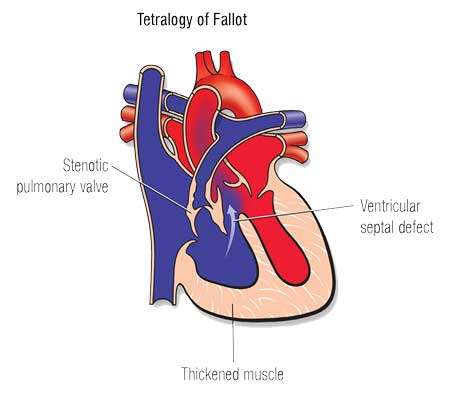

Tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is characterized by four distinct heart anomalies that prevent oxygen-rich blood from circulating normally throughout the body. Tetralogy of Fallot is one congenital heart disease that appears at birth. In medicine, the occurrence of all four of these disorders is referred to as tetralogy. The following four cardiac defects are present in a newborn with tetralogy of Fallot:

- Pulmonary stenosis, a narrowing of the vein or artery that connects the heart to the pulmonary arteries.

- Ventricular hypertrophy, characterized by a gradual expansion of the right ventricle.

- Aortic dislocationis when the aorta, the body’s main artery, emerges from the right rather than the left side of the heart.

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD): A hole between the bottom left and right pumping chambers of the heart is known as a ventricular septal defect (VSD).

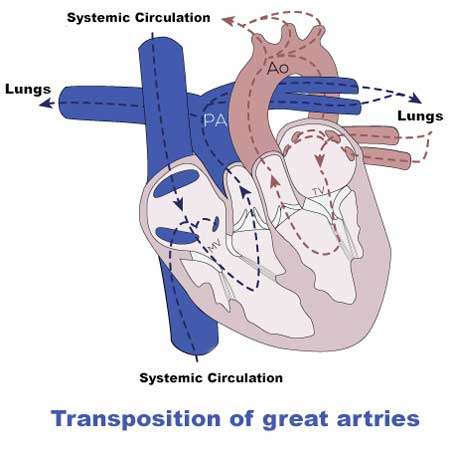

Transposition of great arteries

When the aorta and pulmonary arteries are switched positions in the heart, a condition known as d-TGA occurs, the arterial switch operations used to treat this heart condition at The Heart Center have a very high success rate.

d-TGA is a rare type of congenital heart disease that manifests at birth. Because the arteries are now misaligned, blood no longer circulates normally to the lungs and the rest of the body. As a result, your baby’s organs, muscles, and tissues will receive insufficient oxygen.

Several cardiac abnormalities, including atrial septal defect, have been reported in d-TGA infants.

- Atrial septal defect: A gap between the heart’s upper pumping chambers or atria.

- Ventricular septal defect: A veno-arterial malformation is a hole in the heart’s wall that separates its two bottom pumping chambers (ventricles).

- Patent ductus arteriosus: Opening at the pulmonary artery to the aorta

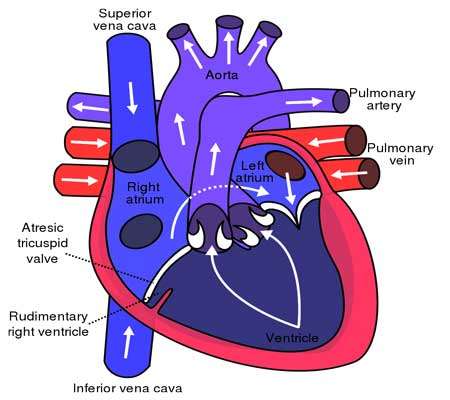

Tricuspid Atresia

Tricuspid atresia is an uncommon heart defect that destroys the valve between the atrium (the upper right chamber of the heart) and the tricuspid valve (the lower right chamber of the heart) (the ventricle). Tricuspid atresia is a congenital disability involving only one of the heart’s valves. Tricuspid atresia can cause a variety of heart problems in children.

- A missing tricuspid valve

- A small right ventricle

- The right and left atriums are connected by a hole, allowing blue and red blood to mix inside the heart, and the right ventricle is abnormally small.

A gap in the wall between the right and left ventricles is common in children with tricuspid atresia. As a result of the abnormal blood flow caused by these heart disorders, the child may develop other health problems. After delivering oxygen to the rest of the body, blood returns to the right side of a healthy heart.

The term “blue blood” refers to oxygen-depleted blood. The red blood cells return to the body via the right side of the heart after oxygenating in the lungs, carrying the blue blood back to the heart. The left ventricle of the heart returns oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. Blood flow through the heart may be abnormal in a child if he or she has tricuspid atresia.

Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return

In patients with total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR), the heart has more difficulty pumping blood with oxygen to the rest of the body. A healthy heart will send blood to the lungs to be oxygenated. The pulmonary veins then return this blood to the heart’s left side, distributed throughout the body. TAPVR appears due to abnormal fetal heart growth between weeks 4 and 6. The pulmonary veins are switched to the wrong side of the heart in a child with TAPVR. As a result, the body cannot effectively use the oxygen stored in the lungs.

Truncus arteriosus

It is a congenital heart defect that affects children. Each year, approximately 250 infants are diagnosed with Truncus Arteriosus; however, due to the severity of this condition, they must receive care from cardiologists experienced in dealing with it. Every year, hundreds of infants born with serious heart defects such as truncus arteriosus can be cured after surgery.

Only one large blood vessel branches off from the heart in a baby born with truncus arteriosus rather than two smaller ones. Truncus arteriosus is a relatively uncommon form of congenital heart disease. The blood channel leading away from the heart will branch off to become the following blood vessels as the fetus develops inside the mother’s womb:

The pulmonary artery carries oxygen-depleted blood from the heart to the pulmonary arteries. The truncus arteriosus prevent this. The heart is supplied with blood by a single major artery. As a result, oxygen-rich and oxygen-depleted blood mix. As a child’s blood flows through his or her body, it will carry less oxygen. Too much blood is being sent to the lungs, which increases the breathing rate and puts additional strain on a child’s heart. A potential health risk is pulmonary hypertension. A hole exists between the bottom left and right pumping chambers of the heart in a child with truncus arteriosus (ventricles). A ventricular septal defect is a gape in the heart’s wall (VSD).

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS)

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome a congenital disability in which only one of the heart’s ventricles develops normally is hypoplastic left heart syndrome. The left ventricle (a pumping chamber) of a child with hypoplastic left heart syndrome is too small to efficiently deliver oxygen-rich blood to the body.

The right ventricle is the only chamber in the human body that pumps blood. The aorta transports blood from the heart to the rest of the body, begins with a very short segment. As a result, a child’s organs and tissues do not receive enough blood and oxygen to function normally. In some places, the left side of the heart is underdeveloped or undersized:

Congenital heart disease treatment

The type and severity of the defect determine treatment for a congenital heart defect.

- Cardiac catheterization can be used to repair minor problems such as a hole in the heart’s inner wall.

- Catheterization is the insertion of a thin tube into the heart through a vein.

- Surgery may be required to correct problems with the heart and blood vessels.

- A heart valve replacement or repair procedure.

- A device is implanted in the chest to assist the heart in pumping blood throughout the body.

- A heart transplant surgery to accomplish this illness. If your child has a patent ductus arteriosus or a congenital heart defect, he or she may be prescribed medication.

Whether or not their condition has been corrected, children and adults with congenital heart defects require regular cardiologist checkups (a physician specializing in heart issues). Some patients may require several cardiac procedures or catheterizations throughout their lives. They may also need medication to help their hearts function efficiently.